CALIFORNIA.SYSTEMS

CALIFORNIA.SYSTEMS

California, IT, Vintage Computing, Earthquakes

This is a personal website unaffiliated with any office, agency, or service of the State of California.

San Andreas Fault

[ Next ] [ Top ] [ Bibliography ] [ Home ] [ Site Map ]In 2022, I got the idea to see the San Andreas Fault.

My work dispatched me to Indio which, somehow, I knew was two miles from the fault. Figuring it was a landmark as conspicuous as any feature, like Mount San Jacinto or Mono Lake, I decided to try and see it. So I casually searched "San Andreas Fault" on Google Maps and got no results in Indio or the surrounding area.

Puzzled, I searched "San Andreas Fault Interactive Map" on the web, first encountering David K. Lynch's Google Maps overlay. David K. Lynch is a local scientist, not the film director. I dropped the little yellow "Street View" man on the 10 precisely where Lynch's map indicates a fault crossing. My heart pounded and my stomach churned with anticipation. But as the pixelated blur slowly gave way to a perceptible image, I panned around confused, seeing only desert and trucks.

- Reference: David K. Lynch's map

- A better United States fault map (which I did not find that day): U.S. Quaternary Faults

I continued on like this for a while, dropping the Street View man at various fault crossings in the Indio area.

Three things then occurred to me: that I had no idea what I was looking for, that the fault is not a conspicuous feature, and that roads on the fault trace are often in noticeably bad shape compared with surrounding roads. The first two observations disappointed me and could very well have forever discouraged my quest, but the third fact intrigued me just enough to keep me hunting. Feeling sheepishly out of my element, I started googling things like "what does the San Andreas Fault look like?" and "visit the San Andreas Fault in Indio." By now work had cancelled my dispatch, but the first natural feature that I learned to associate with the fault planted the seed of feverish obsession.

The San Andreas Fault approaching Wrightwood. It

is unkind to roads, but otherwise not abundantly apparent.

The San Andreas Fault approaching Wrightwood. It

is unkind to roads, but otherwise not abundantly apparent.

The San Andreas Fault creates desert oases! In the Palm Springs area, California's seismic adversary occasionally expresses itself with linear swaths of palm trees, greenery, and trickles of fresh mineral water (occasionally pooling in little "sag ponds"), collectively standing out against the surrounding hellish desertscape. The largest and most picturesque of these is easily the Thousand Palms Oasis, a large pond of shimmering rainbow-streaked freshwater teeming with grass chutes, scrub, greenery, and an astoundingly dense palm grove to which desert fauna cling for dear life. One would be forgiven for thinking it's a photoshopped vision of a Looney Tunes style desert "mirage:" all that's missing is a goddess in a white, gold-braided chiton bringing you a silver pitcher of ice water.

Oh, and just to get this out of the way: the San Andreas Fault is not a gigantic fissure spewing hell's flames. While I certainly knew better than at least this, I must confess that the fault's subtlety caught me off guard more than anything. It's devilishly deceptive.

Thousand Palms Oasis, underlaid by the San Andreas Fault.

It may be apparent by now that I have no education in geology. In fact, until I started dropping Street View in search of the San Andreas, I had absolutely no interest in geology, let alone the outdoors. This is perhaps because I grew up nestled in the South Bay area of Los Angeles County, the spot of LA urban sprawl furthest from any exit from LA's monstrously broad borders. Growing up here, until you leave LA for the first time, you have no reason to think there exists anything but continuous low-density city.

And yet I was instantly hooked. Overnight my vocabulary expanded, even if I struggled to grasp the concepts. I dropped Street View at dozens of fault crossings up and down the state, convincing myself I saw such things as scarps, sag ponds, fault gouge, pressure ridges, and right-lateral offset in roads. It takes a long while, but one eventually develops an intuition for what the fault feels like, visually, at least where it isn't shy to express itself. I found favorite locations to view the fault, scratched my head at other crossings where I just couldn't see it, and came to marvel at the forces which built the land I love... and shake it up violently when they feel like it.

All this from poking around in Google Street View with fault maps and reading geology articles. I owe a great debt to Google's Street View project.

I eventually started taking trips to see the fault in person. Since November 2022, I've followed the fault, over multiple road trips, from Bombay Beach to Daly City. I aim to complete my visits, even to someday visit its northernmost presence on land near Cape Mendocino.

Trip 1 - Cajon Pass-Wrightwood-Valyermo

[ Next ] [ Top ] [ Bibliography ] [ Home ] [ Site Map ]Completed: November 26, 2022

I took my first itinerary largely from Geology Underfoot in Southern California's 19th "Vignette"1, assisted by the BackroadsWest Trips Blog "San Andreas Fault Tour near Wrightwood"2. They're essentially the same trip: they "acquaint" you with the fault at Lost Lake, a "sag pond" in Cajon Pass; take you through Lone Pine Canyon to the snowy mountain town of Wrightwood; and back down the mountain to Valyermo in the Mojave Desert, where you inspect a trench dug into the fault to read its earthquake history. Even without any geologic knowledge, you see quickly that, when following the San Andreas Fault, you encounter manically rapid changes in biomes and topography.

Cajon Pass is the storied mountain pass to Los Angeles, through which Mormon settlers notably traveled3,the historic Route 66 once zipped4, and by which Angelenos now, by way of the 15, access the Sierra Nevada and Las Vegas. It is also a vital transportation corridor criss-crossed with three rail lines5, accommodating most of the shipments which enter the US through Terminal Island. Geology Underfoot's 11th Vignette describes neatly the complex and incredible birth of this "gift from nature," and it's a long story. The best I can do is to oversimplify the two central details while emphatically stating a lot more was at play: the San Andreas Fault provided the local Cajon Creek with easily eroded material, and Cajon Creek followed it happily. Some 500,000 years of this, and bam. Cajon Pass7.

Lost Lake is a "sag pond" between two "scarps" of the San Andreas Fault8, so named because the land around it conceals it. You won't see it from the parking lot, as one of these fault scarps blocks your view. Sag ponds form where water collects in the lower depressions along a strike-slip fault9. This happens almost continuously along the trace of the San Andreas10; they're therefore a great way to quickly spot the fault over a long distance. And scarps, short for "escarpments," are sharp, linear cliffs ranging from a few feet to thousands of feet high, often created by faulting11. A cliff pushed up in the 1992 Landers Earthquake (M7.3) provides a dramatic visual example of with what violence and suddenness these can form!12

A fault scarp, a sort of cliff, pushed up by the Emerson Fault in the 1992 Landers Earthquake (M7.3)! Many scarps, now in varying states of erosion, follow the San Andreas Fault. Image source: Earthquake Science Center, USGS12

A fault scarp, a sort of cliff, pushed up by the Emerson Fault in the 1992 Landers Earthquake (M7.3)! Many scarps, now in varying states of erosion, follow the San Andreas Fault. Image source: Earthquake Science Center, USGS12

My dad, a passionate mountaineer and hiker with a much greater love for the outdoors than me, came along. At several stops he indicated myriad features, mostly mountains and creeks, that I may never hope to remember. It was also my first real encounter with the San Andreas Fault. For his presence, and for it being the first, I remember the trip extremely fondly.

We left the LA area expediently by way of the 605, up to the 10 or 210, I can't remember which. As we left in the early morning, the usual traffic did not hold us. Then we jetted, as the desert locals put it, "over the hill," basically through Cajon Pass. Through a couple of backroads, one unpaved, we made our way to the Lost Lake parking area.

Approaching this place I felt anxious: I had a date with my mortal terror, after all. There's a claustrophobic feeling in "bottoming out" at the low point of Cajon Pass. It's a lot like the moment a track-guided boat on any Disneyland water ride, descending its platform, begins to float in water. The rocky Swarthout Canyon Road, which crosses three back-to-back rail lines with no signal, only compounds the anxiety. Then take the strangeness of the features. You have mountains all around you in a chaotic arrangement, because they're literally in the process of being shifted. Given the haphazardness of everything's placement, I'd compare navigating the area with getting through furniture rearranged so someone can vacuum a room. Now add an awareness that the San Andreas Fault lurks beneath, and tell me your heart rate isn't rising.

The strange bit was arriving. I parked, my dad and I got out, and since we couldn't see the pond, we wondered if we were in the right place. We walked over the fault scarp oblivious to its presence, and there was our destination: a tiny elongate pond aligned roughly with the surrounding linear canyon, pointing to the northwest. All my anxiety deflated in that moment. I knew the plate boundary must be beneath my feet. I thought, in walking around this pond, perhaps I'm crossing continents multiple times. The last thing I expected, however stupidly obvious it is in hindsight, was for the experience to feel serene. Lost Lake is pleasant and picturesque, oddly green compared with its surroundings, and profoundly quiet for being a potential major earthquake epicenter.

My first direct view of the San Andreas Fault. This day, I finally learned that the fault is visible mostly through its effects (i.e.: indirectly).

My first direct view of the San Andreas Fault. This day, I finally learned that the fault is visible mostly through its effects (i.e.: indirectly). Me standing before my worst fear. A calm quickly came over me as I realized the Big One probably wasn't coming during my visit.

Me standing before my worst fear. A calm quickly came over me as I realized the Big One probably wasn't coming during my visit. The low linear ridges on the far right are fault scarps8, each one probably pushed up in a single earthquake! The surrounding landscape is low and very linear, and points directly to Lone Pine Canyon at the end. Reviewing my photos, I'm surprised to see I got this, as at the time I understood none of this.

The low linear ridges on the far right are fault scarps8, each one probably pushed up in a single earthquake! The surrounding landscape is low and very linear, and points directly to Lone Pine Canyon at the end. Reviewing my photos, I'm surprised to see I got this, as at the time I understood none of this.This pattern persisted through my subsequent trips. The fault is a sublime artist. There's not an undeveloped bit of land along its trace which doesn't stun you with its beauty and arrest you with its silence.

My dad picked up a rock inset with several crystals. He asked me if I had any interest. I didn't. I regret now that I let him throw it back.

We set out for Wrightwood, deviating only slightly from the planned itinerary. As we found the rocky Swarthout Canyon Road too rough for my Honda Accord, we returned to the 15 and found another way to Lone Pine Canyon Road. This we followed through the eponymous canyon, as long and linear as anything along the San Andreas Fault. We stopped at a turnout marked by, as Geology Underfoot puts it, a "very serious white gate"13. The stop afforded us a breathtaking view of the procession of mountains straddling the fault. Being the mountaineer, my dad's eyes lit up. He hopped around with a boyish excitement, snapping photos and pointing to and naming various peaks. It warmed my heart, seeing him in his element. My own passion for the outdoors was still lukewarm; the San Andreas hadn't yet brought it to a simmer.

I took this photo from the same location as the crack in the road shown at the beginning of this article. I only suspected it at the time, but can confirm now that, from this vantage point, I'm standing directly on top of the fault, looking to the southeast along its trace. Check my coordinates against the fault maps! 34°20'31.5"N 117°36'09.4"W

I took this photo from the same location as the crack in the road shown at the beginning of this article. I only suspected it at the time, but can confirm now that, from this vantage point, I'm standing directly on top of the fault, looking to the southeast along its trace. Check my coordinates against the fault maps! 34°20'31.5"N 117°36'09.4"WBy now hunger started to set in, so we were grateful to find Wrightwood - and its Grizzly Cafe - a short drive away. Remember that most of our morning went to leaving Los Angeles. Once in Wrightwood, we took the detours recommended in the BackroadsWest blog2. The first is Wrightwood Country Club, which utilizes a sag pond of the San Andreas Fault as a swimming pool!! Apparently filling it in with a little extra water and adding some tile was all it took. Considering the risk of surface rupture, I shudder to imagine swimming in this pool when the inevitable happens. When we finished shaking our heads in bewilderment, we drove through town, observing with some consistency the linear depression that marks the streets. At this time I think I was more in my element than my dad, I being the disaster-obsessed one. But I finally listened to our stomachs and drove us to the Grizzly Cafe, which in itself is justification to visit Wrightwood.

I don't want to start any personal wars, as I'm fond of Wrightwood. But I do invite the Wrightwood Country Club to explain to me why this isn't a terrible location for a swimming pool.

I don't want to start any personal wars, as I'm fond of Wrightwood. But I do invite the Wrightwood Country Club to explain to me why this isn't a terrible location for a swimming pool.Over a filling meal, my dad and I read through Geology Underfoot's 19th Vignette1. Southern California's last "Big One," the M7.9 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake, was relevant to the stops ahead of us. Of the temblor's effects they said, "the 1857 earthquake rupture cut through Wrightwood long before modern development. Several mature pine trees grew right on the fault trace back then. The fault rupture tore up their root systems so severely that the trees' growth was stunted for several years [ . . . ] these same trees were also shaken with such a force that their tops snapped off as they were whipped violently back and forth14." (!) The Fort Tejon Earthquake, technically centered in what is now Parkfield, was a prodigious monster of a quake. Perceptible shaking was reported from north of Sacramento down to San Diego and as far east as Las Vegas, surface offsets reached 30 (!) feet in the Carrizo Plain, and severe effects including fissuring and sunken trees were reported from Sacramento to near the Mexican border15. It's only because Southern California was sparsely populated that this event is associated with little property damage or fatalities16.

Geology Underfoot added ominously, "Wrightwood will not fare well when the next large earthquake occurs on this segment of the San Andreas Fault14."

Nourished, and with these comforting thoughts, we set out for Valyermo with several planned stops. The first was the Big Pines Visitor Center just out of town, originally built to bid for the 1932 Winter Olympics (sadly, they went to Lake Placid, New York) 17. Stairs from the visitor center, which ascend a towering fault scarp, provide access to campgrounds and the Mountain High Trail. Geology Underfoot indicates this scarp probably formed in the 1857 earthquake17. Backroads West adds that the impressive stone tower marks the highest point of land along the San Andreas Fault2. I further have it from disparate sources, including talkative Wrightwood locals, that the tower was originally part of an arch spanning the street.

This stone tower is the surviving end of an arch which once spanned the Angeles Crest Scenic Byway. It also marks the highest point of land along the San Andreas Fault2.

This stone tower is the surviving end of an arch which once spanned the Angeles Crest Scenic Byway. It also marks the highest point of land along the San Andreas Fault2. A fault scarp of the San Andreas made a convenient place to build stairs. I'm standing on the stairs; these retaining walls I can only suppose keep the scarp from collapsing onto the road.

A fault scarp of the San Andreas made a convenient place to build stairs. I'm standing on the stairs; these retaining walls I can only suppose keep the scarp from collapsing onto the road.Geology Underfoot also suggests keeping an eye out for split trees, as a few survivors of 1857 still stand here. They caution that younger trees are likely damaged by lightning, but forks halfway up the trunks of older trees could be the scar of that terrible earthquake14. Writing this just now, I terrified myself imagining the singular event which likely pushed up this scarp and snapped tops from the trees around me. I'm glad I was not standing here when it happened, and I question my sanity that I am so eager to visit the fault.

The second foreground tree from the left forks a little less than halfway up its trunk. It may be a survivor of 1857, and the fork may be its scar.

The second foreground tree from the left forks a little less than halfway up its trunk. It may be a survivor of 1857, and the fork may be its scar.Continuing our itinerary, we took Big Pines Highway down to Jackson Lake. Both guides recommend their own stops along the way to see fault gouge, BackroadsWest adding a massive gorge notched by the fault2. Though as the day progressed we found the mountain roads increasingly overrun with adult children playing Initial D in supercars, so it was challenging to quickly and safely stop for turnouts. I saw one desirable landmark, a fin-shaped pile of gouge, pass us by, and regret passing it again on a second return trip to the area. But I did at least get a shot of tilted layers mentioned in none of my books! Tilted and stratified layers, at least in the context of tectonics, are associated with compressional forces in synclines, anticlines, and monoclines18; I have to believe something similar is at play here.

I passed the best site to view this gorge, though I think my view illustrates its immensity well enough. My regrets bringing only my cell phone camera.

I passed the best site to view this gorge, though I think my view illustrates its immensity well enough. My regrets bringing only my cell phone camera.

Steeply tilted layers mentioned in none of my books! I did not note the exact location, but it must be on the Big Pines Highway just shy of Jackson Lake, given its placement in the gallery.

Steeply tilted layers mentioned in none of my books! I did not note the exact location, but it must be on the Big Pines Highway just shy of Jackson Lake, given its placement in the gallery.We continued to Jackson Lake, another sag pond. It seems there's an unspoken tradition of naming the San Andreas' sag ponds "lakes." We found the water partially frozen over and snow kissing the banks. The pond is formed by a shutter ridge and has been artificially expanded for recreational use19. David K. Lynch defines a shutter ridge: "a ridge, usually a pressure ridge, that has been shifted across a stream by transform faulting. Shutter ridges block streams, often creating offsets in the flow20. Jackson Lake ranks among the more deceptively picturesque scenes along the San Andreas Fault. Surrounded by coniferous trees and with a touch of real winter setting in, I felt like I was standing on a set for The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser. I couldn't imagine that we were in Los Angeles County, let alone that the Mojave Desert was 20 minutes down the road!! Let me repeat with what manic rapidity you pass through extreme biomes and topography along the San Andreas Fault.

Jackson Lake. Minus the power lines, it's difficult to imagine this isn't the scene from a continental 19th century romance. Let me shock you with this: it's in Los Angeles County.

Jackson Lake. Minus the power lines, it's difficult to imagine this isn't the scene from a continental 19th century romance. Let me shock you with this: it's in Los Angeles County. My dad poses before Jackson Lake. Both of us stand atop the San Andreas Fault, California's deadly seismic adversary.

My dad poses before Jackson Lake. Both of us stand atop the San Andreas Fault, California's deadly seismic adversary.Our next stop was Pallet Creek, in the Mojave Desert. For some reason, the descent felt like a long journey with lots to talk about, but it was very brief with no stops. Even if you don't blink the transition from alpine snow country to desert will happen before you notice. We looked back at the mountains, marveled at the paradoxical juxtaposition in biomes, passed the aptly-named St. Andrew's Abbey in Valyermo, stopped at the mile marker 0.76 on Pallet Creek Road, and walked right out into thick brush. No trail or sign guides you to the excavation site; it took splitting up to find it. We descended a moderately frightening precipice, and there it was. Several sedimentary layers laced with peat, broken up by centuries of earthquakes. Geology Underfoot observes, "by radiocarbon dating of peat beds, [Kerry Sieh, a legendary geologist] was able to determine when prehistoric fault displacements occurred." He found that nine 1857-sized earthquakes affected this location since AD 50021. For this short hike I had forgotten my camera phone, so my dad took a photo.

This area is remote, silent, and eerie to visit. The descent into the creek below seems just steep enough that a fall would be injurious, and with a raw San Andreas Fault staring you back more clearly exposed than anywhere along the trip thus far, the fault's silence here is just oppressive enough to curdle your blood.

Staring at the fault trace, I expanded my hands facetiously and said "boom." My dad frowned. Not funny.

"Let's get out of here," he said. I responded, "yeah."

We didn't run to the car, but we didn't walk, either.

I took this photo from Pallet Creek several months after our trip, approaching the summertime. I'm looking back at the San Gabriels, showing the rapid change from desert to snowy mountains. The lush greenery to the right stands out against the hellish desertscape. It clings to Pallet Creek, and to some extent the San Andreas Fault, for life.

I took this photo from Pallet Creek several months after our trip, approaching the summertime. I'm looking back at the San Gabriels, showing the rapid change from desert to snowy mountains. The lush greenery to the right stands out against the hellish desertscape. It clings to Pallet Creek, and to some extent the San Andreas Fault, for life.

My dad's photo of Kerry Sieh's trench at Pallet Creek. The material here is shockingly brittle, and I feel bitterly guilty having touched it just enough to discover this.

Pallet Creek concluded Geology Underfoot's 19th "Vignette" and the BackroadsWest's recommended itinerary, but as the Vasquez Rocks were a short drive away, and the return drive to Los Angeles was guaranteed misery anyway, we agreed to see them before going home. The Vasquez Rocks are an apocalyptic-looking outcrop of tilted sandstone22 uplifted by the San Andreas Fault's activity23. They take their name from Tiburcio Vasquez, a Californio bandido who hid in these rocks' deep crevices and caves to avoid law enforcement23. Today they are famous as a television set, rendered legendary by their use in the Star Trek episode "Arena" (the one with the Gorn) and widely used thanks to their dramatic appearance and short distance from Los Angeles. Wikipedia maintaints a partial list of productions featuring the rocks24.

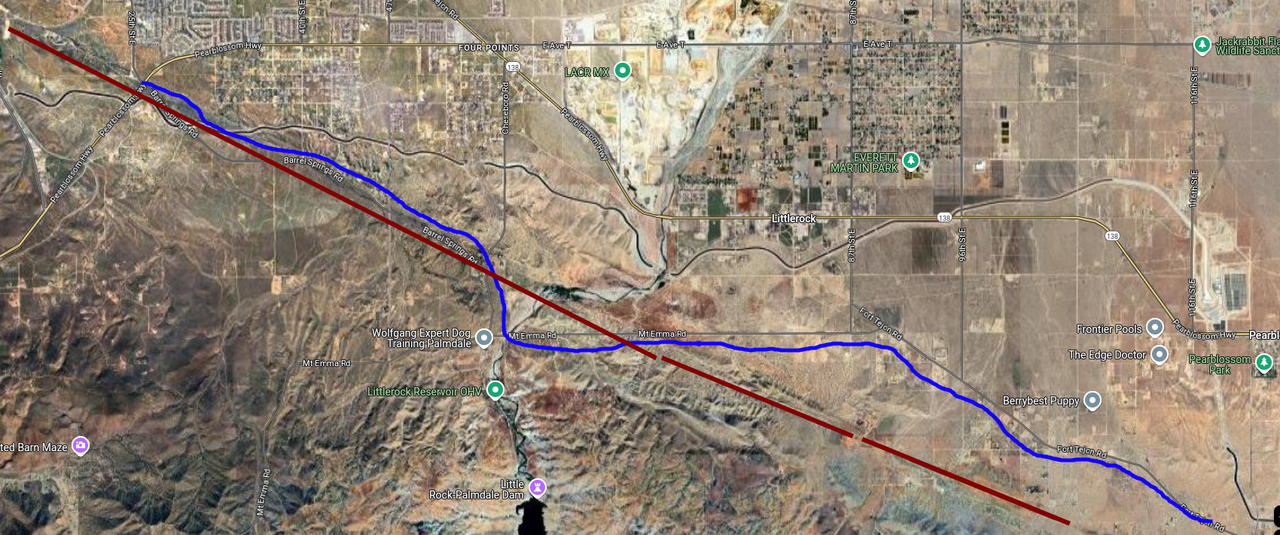

Since we started from the middle of nowhere, we followed a series of backroads cutting roughly diagonally across the desert. It felt like a long drive to the 14. I only suspected it at the time, going by reflections on what we'd seen that day and the peculiar linearity and straightness of the topography, but we followed the San Andreas Fault almost the whole way. Quite literally: we took Fort Tejon Road to Mount Emma Road, switched to Barrel Springs Road at a point, and followed this all the way to the 14.

Star Trek seems to be the kernel of my dad's childhood, and the Vasquez Rocks hold a dear place in his heart. On the way, he told me an amusing story: in childhood. his dad drove him through this area. My dad was seated in the back seat. Like a flash, he saw these rocks pass and became excited. He shifted around in the back seat hurriedly, as children do, bobbing his head around and really shaking up the car trying to get another glimpse of them. His dad shouted at him, "what are you DOING???" He replied, "that was on Star Trek!" and continued scrambling for a view. His dad repeated, "what are you DOING???"

The Vasquez Rocks are featured in countless films and television programs going back to at least the 1930s, though they are perhaps best remembered and most beloved as this Star Trek set.

The Vasquez Rocks are featured in countless films and television programs going back to at least the 1930s, though they are perhaps best remembered and most beloved as this Star Trek set.The sun was reclining and the monotony of driving was starting to wear. Getting on the 14 it already felt like LA traffic, so the final trip was welcome. I recall that, on the way in, we passed a massive Ford F150 towing a trailer probably twice its own length, and that there was not enough room for it to clear the little dirt path to the parking lot. The driver and her front seat passenger both had their windows down and shouted at everyone passing, making polite gestures and blaming just about everyone but themselves for the traffic jam that resulted. What can I say? Their ugly behavior was amusing and a nice first contact with civilization.

Quite the contrast to Pallet Creek, the Vasquez Rocks were popular! Everyone and his brother seemed to be vying to pose in front of or climb the rocks, including a massive family in wedding garb. My dad helped a friendly older visitor up the rocks, apparently to live her childhood dream. On the way down she helped him get a start. They both made me nervous climbing so high! But I'll nevertheless forever remember their infectious excitement and the gleam in their eyes. I climbed the rocks myself; getting down was harder than getting up.

My dad climbs the Vasquez Rocks, realizing a childhood dream.

My dad climbs the Vasquez Rocks, realizing a childhood dream.Footnotes

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 207-220.

- Bandringa, "San Andreas Fault Tour Near Wrightwood."

- US Forest Service, "Mormon Rocks Interpretive Trail."

- National Park Service, "Cajon Pass."

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 103.

- "Cajon Pass," Wikipedia, last modified September 21, 2024.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 103-115.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 209-210.

- "Sag Pond," Wikipedia, last modified October 20, 2022; Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 358.

- "Sag Pond," Wikipedia, last modified October 20, 2022;

Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 309;

Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 207-220;

Lynch, Field Guide To San Andreas, 44. - Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California,"359.

- Earthquake Science Center, "Landers Fault Scarp."

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 211.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 214.

- Earthquake Hazards Program, "M7.9 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake."

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 207.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 215.

- Lynch, Field Guide To San Andreas, 45.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 216.

- Lynch, Field Guide To San Andreas, 200.

- Sylvester et al., "Geology Underfoot In Southern California," 219-220.

- Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 308.

- "Vasquez Rocks," Wikipedia, last modified September 15, 2024.

- "Productions Using Vasquez Rocks," Wikipedia, last modified August 12, 2024.

Trip 2 - Palmdale

[ Next ] [ Top ] [ Bibliography ] [ Home ] [ Site Map ]Completed: March 18, 2023

My second trip was short and sweet. My work dispatched me to a Chatsworth customer to shut down and bring up servers for a limited power outage. There were a few hours to burn while waiting for power to return, but not enough to go home (I took the 405). I got coffee at Northridge Mall but quickly grew bored of the surroundings. My options for entertainment were a Dave N. Busters, a Men's Warehouse, and a whole lot of nothing else. I had only the novelty of the location's seismically weighty name to amuse me. But looking north along the streets, I saw the San Gabriels. They beckoned to me.

I pulled out Google Maps and started toying with routes. I found that Lake Palmdale, a water reservoir in the San Andreas Fault, was an hour away. As I searched, I pinged my dad on gChat. He observed anecdotally that there are a lot of thrust faults along the 14, and you can see them in the mountains. I'd heard this before, so this sealed the deal for me. I got in my car and hit the road.

The 14 meets the 5 at Newhall Pass, another precious break in the Transverse Ranges. This is the T-junction which collapsed dramatically in the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake (M6.6)1 and again in the 1994 Northridge Earthquake (M6.7)2, a violent history which is likely to repeat itself. From here the 14 cuts through the Transverse Ranges and down into the Mojave, where it joins the San Andreas Fault in Palmdale3. The stretch of San Andreas bounding these mountains behaves differently than along most of its run: here, thanks to the plate boundary's boomerang shape, the Pacific and North American plates collide mostly head-on, rather than simply grinding past eachother. Continental collisions push up mountains by way of thrust faults, hence, the Transverse Ranges and LA Basin are rendered brittle underground, and we get occasional local earthquakes4.

Sections of the 5/14 interchange failed catastrophically in the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake1 and again in the 1994 Northridge Earthquake2. Image source: NOAA NGDC via Wikimedia Commons 5.

Sections of the 5/14 interchange failed catastrophically in the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake1 and again in the 1994 Northridge Earthquake2. Image source: NOAA NGDC via Wikimedia Commons 5.

This drive was impromptu and I was still new to all this, so I had no clue of what to look out for. There are also no safe places to stop along the 14, and the motorists here are FAST, so it was difficult to take anything in. Roadside Geology describes a lot on this route6, though most of it I can't recall. They do acknowledge that there's folding, faulting, and tilting7 visible, at least initially, which I did see. But even they found the 14 too fast with too few places to stop, and so instead referred to several nearby alternatives on The Old Road and at the Vasquez Rocks.

That's not to say the drive wasn't interesting! There's just little I can account for with any confidence until Palmdale. So, on to the Big Sister.

The San Andreas Fault nicks the southern border of Palmdale3, and perhaps not so curiously, the southern end of the town's development adheres roughly to its trace. The attractive San Andreas feature here is the Palmdale Roadcut, a blast through a pressure ridge of the fault which exposes intense compression, folding, and a fault scarp. Roadside Geology observes, "the main fault is at the south end of the roadcut; a strand of the San Andreas Fault, the Littlerock Fault, lies at the north end of the roadcut. Extreme deformation of the sedimentary layers is a consequence of being squeezed between two faults."8. The intense compression is visible on either side of the 14, but only for a moment when you zip by at 70. Look out for it right past the Avenue S exit when going north.

From Michael R. Perry on Flickr. A beautiful shot of the Palmdale Road Cut exposing intense folding of the sediment 9. As I found no safe way to access this vantage point, I only managed a speedy passing glimpse from the 14.

From Michael R. Perry on Flickr. A beautiful shot of the Palmdale Road Cut exposing intense folding of the sediment 9. As I found no safe way to access this vantage point, I only managed a speedy passing glimpse from the 14.

David Lynch offers backroads to vantage points to see the east and west face of the roadcut10, as do some scattered blogs. I didn't have this information on me and the little driving I did in town turned up fenced private property and nosy police patrols whose attention I didn't want to attract. Palmdale is home to the Edwards Air Force Base, so best to avoid strange activities here. I snapped some photos of the mountains, then resorted to seeing Lake Palmdale.

Mountains seen from Palmdale. They were conspicuously linear and northwest-trending.

Mountains seen from Palmdale. They were conspicuously linear and northwest-trending.

I pulled into a bowl-shaped parking lot that seemed to be perpetually falling away from me. I mean, it's like being in a funhouse, where they use optical illusions to constantly play with your sense of perspective. In this way, the Lake Palmdale parking lot is tremendously interesting, and I am not being facetious about this. The tarmack clings to a peculiar topography.

At the center of all this is a water reservoir which, as I've heard second-hand, fills a natural sag pond of the San Andreas. It doubles as a private fishing and duck hunting club11, otherwise closed to the public. But the poor ducks will be avenged: an historically active trace of my pet fault grazes the northeast corner of the reservoir3, leaving visible cracks in the parking lot before continuing on to the above-mentioned roadcut. Someday it will open its gaping maw and swallow the hunting club whole, the ducks flying away free and never to be harmed again.

Note: I'm merely being figurative. The fault doesn't "open," let alone swallow anything.

I sheepishly asked an older local if she was aware the San Andreas was under the lake. She said quite confidently that she was, and I privately questioned my wisdom and decorum in asking a test question like this. She was nevertheless polite: she told me the "strong" earthquakes of the Valley, like '71 and '94, are strongly felt here and thanked me for the chat.

I'd spent enough time away, so I got in my car and returned to Chatsworth, again passing through wild geology that eluded my amateur eyes at 70mph. The fear of the Big One hit me when I got to Avenue S: I couldn't get back on the 14 quickly enough, and was loathe to stop for a red light under the freeway!

Curiously enough, I don't think I saw a single palm tree in Palmdale.

Lake Palmdale, looking south. The San Andreas Fault runs under the northeastern shore (left foreground) and to my approximate location shooting this3. I didn't notice it at the time, but the fence in front of me shows conspicuous deformation at the approximate fault trace. I'll let a geologist tell me, but I don't think it's coincidence.

Lake Palmdale, looking south. The San Andreas Fault runs under the northeastern shore (left foreground) and to my approximate location shooting this3. I didn't notice it at the time, but the fence in front of me shows conspicuous deformation at the approximate fault trace. I'll let a geologist tell me, but I don't think it's coincidence.

Footnotes

- "1971 Collapse," "Newhall Pass Interchange," Wikipedia, last modified July 9, 2024.

- "1994 Collapse," "Newhall Pass Interchange," Wikipedia, last modified July 9, 2024.

- USGS Geologic Hazards Science Center, "U.S. Quaternary Faults," coordinates 34°33'36.9"N 118°07'52.4"W, https://usgs.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=5a6038b3a1684561a9b0aadf88412fcf

- Killer Quake, written and produced by Robert Dean, 25:55-27:56.

- E.V. Leyendecker, Collapse of Newhall Pass interchange, NOAA.

- Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 305-311.

- Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 306-308.

- Sylvester et al., "Roadside Geology Of Southern California," 311.

- Michael R. Perry, The San Andreas Fault at the I-14, Flickr.

- Lynch, Field Guide To San Andreas, 97.

- Palmdale Fin and Feather Club, Inc., accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.palmdalefinandfeatherclub.com/

Bibliography

Sylvester, Arthur G., Robert P. Sharp, Allen F. Glazner, and Elizabeth O'Black Gans. Geology Underfoot In Southern California. 2nd ed. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 2020.

Bandringa, Cliff. "San Andreas Fault Tour Near Wrightwood." BackRoadsWest Trips Blog. October 1, 2015. https://www.backroadswest.com/blog/san-andreas-fault-wrightwood/.

US Forest Service. "Mormon Rocks Interpretive Trail." US Department of Agriculture. 2013. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5391972.pdf.

National Park Service. "Cajon Pass." US Department of the Interior. 2023. https://www.nps.gov/places/cajon-pass.htm.

"Cajon Pass." Wikipedia. Last modified September 21, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cajon_Pass.

"Sag Pond," Wikipedia. Last modified October 20, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sag_pond.

Sylvester, Arthur G. and Elizabeth O'Black Gans. Roadside Geology of Southern California. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 2017.

Lynch, David K. Field Guide to the San Andreas Fault. Topanga Canyon, CA: Thule Scientific, 2009.

Earthquake Science Center. "Landers Fault Scarp." US Geological Survey. 1992. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/landers-fault-scarp.

"Vasquez Rocks," Wikipedia. Last modified September 21, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasquez_Rocks

"List of productions using the Vazquez Rocks as a filming location," Wikipedia. Last modified August 12, 2024. https://w.wiki/BuRN

"1971 Collapse," "Newhall Pass Interchange," Wikipedia. Last modified July 9, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newhall_Pass_interchange#1971_collapse

"1994 Collapse," "Newhall Pass Interchange," Wikipedia. Last modified July 9, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newhall_Pass_interchange#1994_collapse

USGS Geologic Hazards Science Center. "U.S. Quaternary Faults." https://usgs.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=5a6038b3a1684561a9b0aadf88412fcf

Killer Quake. Written and produced by Robert Dean. 1994. Los Angeles: KCET-TV, and Boston: WGBH Educational Foundation. Accessed November 8, 2024. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/KillerQuake/NOVA.S21E16.Killer.Quake.1994.VHSRip.AAC2.0.x264-rattera.mp4

E.V. Leyendecker. 1971 San Fernando Searthquake - Collapse of Newhall Pass interchange. Photograh. 1971. NOAA - NGDC. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NOAA_-_NGDC_-_1971_San_Fernando_Earthquake_-_Collapse_of_Newhall_Pass_interchange.tif?page=1

Palmdale Fin and Feather Club, Inc.. Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.palmdalefinandfeatherclub.com/

Earthquake Hazards Program. "M7.9 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake." US Geological Survey. August 5, 2019. https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/science/m79-1857-fort-tejon-earthquake.

[ Top ] [ Contact Me ] [ Site Map ]